- The House of Wisdom

- Posts

- The Labyrinth That Walks You Back to Yourself

The Labyrinth That Walks You Back to Yourself

Beneath the sacred floor of Chartres lies a path that won’t let you reach the center until you’ve been broken, turned around, and forced to face every part of yourself.

Today's article is written by my friend, Culture Explorer.

He shares stories on some of the most fascinating aspects of culture, history and architecture from all across the world in his newsletter. Before you continue reading, I recommend you check it out below 👇

Most people think a labyrinth is just another word for a maze but it’s not. A maze is a puzzle meant to trick you with choices and dead ends.

A labyrinth has only one path. No forks. No decisions.

Just a winding route that leads you in, turns you around, and brings you to the center.

The idea goes back thousands of years, most famously to the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, where a hero enters a dark, twisting labyrinth to face a monster. But the real power of a labyrinth isn’t about fighting something outside you, it’s about confronting what’s within.

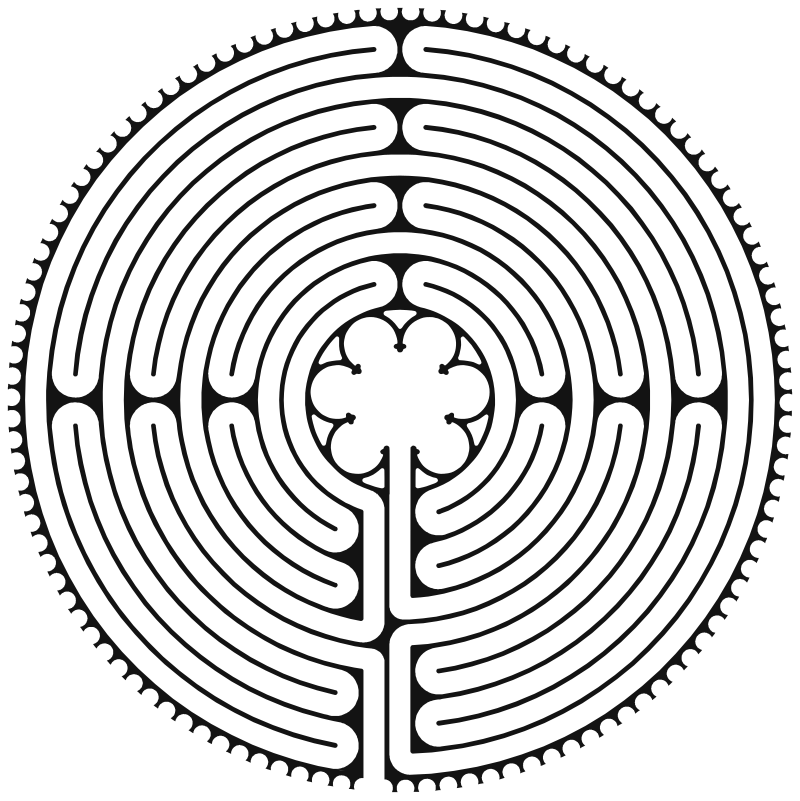

Chartres Labyrinth. Photo is in Public Domain.

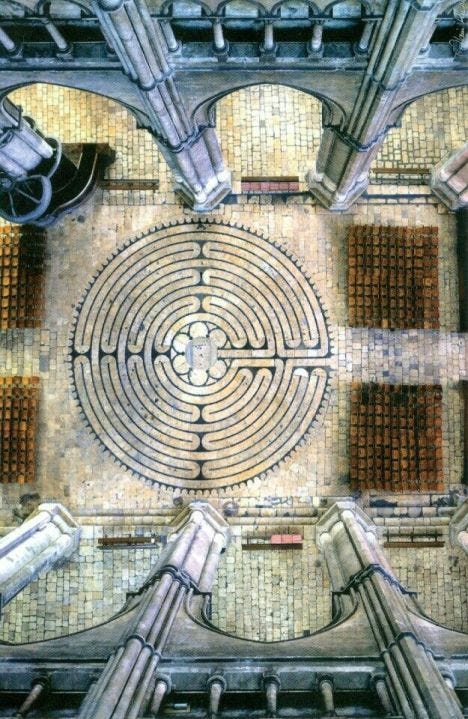

Ancient cultures carved them into temples, traced them on pottery, and built them into sacred spaces as tools for reflection, healing, and prayer. And in a cathedral in Chartres, France, one of the oldest and most intricate labyrinths still waits, etched in stone, pulling in pilgrims the way it has for over 800 years.

Theseus in the Minotaur's labyrinth (1861) by Edward Burne-Jones.

People walk the Chartres labyrinth without realizing what they’re stepping into. They take it for an old floor design; however, it is an 800-year-old code, a medieval puzzle laid in stone, meant to be walked with your feet and solved with your soul.

But here’s the twist: the more you study it, the more it feels like someone hid a mathematical riddle inside a spiritual path. It looks like a circle, walks like a maze, but it’s really a geometric ritual that links faith, symmetry, and psychology.

At first glance, the labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral looks calm, eleven concentric paths coiling inward toward a center. But those lines aren’t random. They form a perfect symmetry that’s deceptive. Pilgrims don’t just walk toward the center; they loop outward, then inward again. The layout deliberately frustrates straight-line logic. That frustration is the point: you have to surrender to the journey, not the destination.

Plan of the labyrinth of Chartres Cathedral. Photo by By Ssolbergj - Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

Unlike mazes, which are multicursal and filled with choices and dead ends, the Chartres labyrinth is unicursal. There’s only one path. You can’t get lost. But it doesn’t feel that way when you’re inside. The winding movement pulls you close to the center, then flings you back out. It’s psychological disorientation disguised as a spiritual metaphor.

Engineers and mathematicians have studied this thing for decades, trying to understand what makes it tick. One of the most striking discoveries comes from flattening it into a square. When you “unfold” the labyrinth, stretch it out like a ribbon, it reveals a pattern of diagonals and turnarounds. These “pilgrim steps” aren’t accidental. They form a deliberate rhythm: two steps forward, one step back. It’s like walking through a life-sized metaphor for human struggle.

Chatres Labyrinth. Photo by David Brazzeal.

The labyrinth's cross-shape is encoded into the path. At three out of four radial branches, the path folds to mirror a cross. But only one branch—the one you enter from—is different. This asymmetry breaks the illusion of perfection and adds depth. The design says: this isn’t just a walk. It’s a pilgrimage. Even if you’re not religious.

The layout also includes six central lobes and outer lunations, which set it apart from similar medieval designs. While other cathedrals—like Amiens or Lucca—used variations of this pattern, Chartres became the definitive model. Its path-to-wall thickness, circular symmetry, and deliberate placement of bends have been copied all over the world.

Chatres pseudo-maze. See footnote 1.

Then there’s the “pseudo-maze” hidden in plain sight. If you ignore the walking path and instead follow the walls, the negative space, you find something different: a three-branched maze with multiple entries and goals. It’s like an Escher trick. The same floor that guides you also deceives you. You can see it as a path or a prison, depending on your point of view.

3-D Chatres Labyrinth Design

And it doesn’t end there. Belgian engineer Samuel Verbiese took this further by shrinking the labyrinth into a smaller seven-circuit version. He kept most of the key features, including the signature “pilgrim’s step.” Then he wrapped it into a cylinder, stacked the cylinders, and created what he calls a “Chartres fractal”—a 3D model of the labyrinth stretching into infinity.

Silver design from Knossos displaying the 7-course "Classical" design to represent the Labyrinth (400 BC). Photo by By AlMare - Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

But where did this design come from?

The roots go back 5,000 years to what’s called the “Classical” labyrinth—a much simpler, brain-shaped pattern made from a seed shaped like a cross. Over time, designers modified that seed: curved it into a circle, flipped the direction of turns, and added a larger central area. One final change—doubling certain elements in all four quadrants—paved the way for the full Chartres layout.

This wasn’t just aesthetic tinkering.

These changes made the labyrinth expandable. You could now build larger versions like the one in Saffron Walden, or even recursive versions like Verbiese’s “infinite” design. The seed became scalable.

And in that seed lies something deeper: the reintroduction of the cross. Around the year 860, a scholar named Heiric of Auxerre recognized that circularizing the classical labyrinth had erased its Christian symbolism. So he brought back the cross, not as a symbol floating above the design, but built directly into the path through meander patterns and mirrored folds.

Amazing Labyrinths. Copyright 2003, 2007 by Samuel Verbiese, Sofam-Belgium.

Today, the Chartres labyrinth has outgrown its medieval setting. Artists have recreated it in parks, sculptures, and digital forms. In Belgium, three permanent versions exist. Others are mowed into grass, walked during festivals, or used in therapy sessions.

The modern revival isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about rediscovery. This isn’t a relic. It’s a living structure that blends geometry, history, psychology, and art. Every turn you take inside the Chartres labyrinth is a confrontation with pattern, with tradition, and with the limits of your own thinking.

And maybe that’s the most radical part. It doesn’t matter what you believe. The Chartres labyrinth forces you to stop walking in straight lines. In a world obsessed with speed and efficiency, it offers something far older: a sacred detour.

The Architecture of Chartres Cathedral

Chatres Cathedral. High Gothic - view from south-east. Photo By Olvr - Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

We talk about modern progress.

But what if we're still living in a Roman world?Because 2,000 years ago, Rome built more than an empire.

It built the foundation of modern civilization.This isn’t nostalgia. It’s fact.

Let me show you how Rome shaped your world 🧵👇— Culture Explorer (@CultureExploreX)

9:10 AM • Jun 9, 2025

Until Next Time,

World Scholar

P.S. Thank You for getting this far! What topic should we dive into next? Let me know directly by replying to this email!

Reply